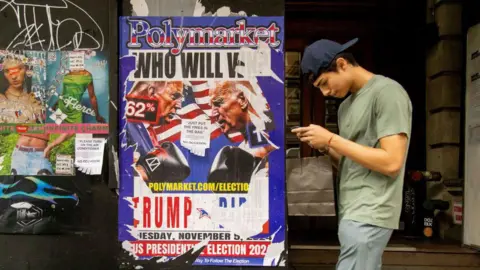

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe director of the longest-running election betting market in modern US politics used to work in a relatively sleepy field, presiding over what he called a “connoisseurs’ market”, where bets were capped at $500 (£388) and no-one made much money.

But the world Thomas Gruca, a marketing professor at the University of Iowa’s Tippie College of Business, now operates in has changed dramatically.

In the last few weeks, as the US barrels towards a presidential election that most pundits and polls say is too close to call, a new crop of companies has exploded on to the scene.

They are attracting hundreds of millions of dollars in wagers on the outcome of the race – and attention from both campaigns and the media, as predictions on many of the biggest sites have tilted decisively in favour of Republican candidate Donald Trump.

The frenzy was in part unleashed in September, when a federal judge rejected arguments from US market regulators that offering election trading to Americans ran afoul of state gambling laws and was not in the public interest.

The decision is being appealed. But since the ruling, more than $100m (£77.5m) has already been wagered on Kalshi, the firm that took regulators to court, according to its website.

Other companies, including Interactive Brokers and the popular stock trading platform Robinhood, have also entered the fray, joining sites that have long served customers outside the US in countries like the UK, where betting on American politics is fair game.

At rallies, Trump has made note of the sudden surge in election betting – and the rising odds of his victory.

His most high-profile supporter, tech billionaire Elon Musk, has also drawn attention to the phenomenon, pointing his social media followers to calls on election betting markets earlier this month, and arguing they were “more accurate than polls, as actual money is on the line”.

Prof Gruca’s Iowa Electronic Markets has very little in common with its new competitors.

The exchange is not tussling with US regulators in court over its legality.

Under rules agreed with the government, it can accept wagers for research purposes, but bets are capped and the exchange is barred from advertising or making money from the activity.

It also oversees a tiny amount of trading, mostly from Americans: a pool of less than $30,000 overall, Prof Gruca said.

There is another big difference.

Unlike bigger platforms like Kalshi, Polymarket, Betfair and PredictIt, where the odds favour Trump by roughly 60% or more, traders on the Iowa market currently have their money on Kamala Harris.

Prof Gruca is proud of his exchange’s track record: on average, over nine elections, the Iowa Electronic Markets has predicted the outcome of the popular vote within almost a percentage point, proving a more accurate guide than the polls.

So he has been surprised by the figures on some of the bigger sites.

“The numbers are extreme – it’s a 50-50 race,” he told the BBC. “We’ve done this for 60-40 races, we’ve seen those before. This is as close or closer than any one we’ve ever seen.”

Sceptical

Betting markets, which have a long history outside the US, have been wrong before: they heavily discounted the odds of a Trump victory in 2016, for example, and thought Republicans would fare better in the 2022 midterms than they did.

But academics say the markets tend to be useful forecasting tools.

Still, Prof Gruca said the public should be sceptical of some of the platforms, noting they don’t have a track record and could be subject to manipulation, given the huge sums of money involved and the risk that the pool of participants is not deep enough to match all bets.

“When you don’t have limits, then it is the deep pockets which moves the prices,” he said. “Your opinion is weighted by the size of your cheque book.”

On Polymarket, for example, big bets from four accounts controlled by a French trader helped to tilt the odds for Trump earlier this autumn.

Researchers have also told reporters they have seen signs on Polymarket of wash trading – that the same people are buying and selling repeatedly, giving the illusion of more activity than there actually is.

Polymarket – which allows users to bet against each other on a specific future outcome and unusually operates using crypto – did not respond to a request for comment from the BBC.

Its chief executive, Shayne Coplan, has previously called the platform a “reality check” and “much-needed alternative data source”, noting that it correctly forecasted that President Joe Biden would drop out of the race.

Others take a darker view.

After the September court ruling, the watchdog group Better Markets warned that allowing such bets would “corrupt the integrity of our elections, trigger market manipulation, and victimise countless investors”.

Prof Gruca said he thought elections bets were a “sideshow” when it came to threats to democracy.

But debate over the issue is likely to continue.

Regulation

In the US, states regulate betting and some have banned election bets outright.

Prediction markets – which differ from gambling because they rely on trading rather than a centralised company overseeing the odds – fall under the jurisdiction of federal markets regulators, who have long taken a dim view of such activity.

But betting norms have been loosening in the US, notably after the 2018 Supreme Court ruling that paved the way for sports gambling.

In May, responding to the uptick in applications from firms seeking to offer trading on events, the Commodities Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) proposed a rule that would explicitly bar trading on political contests.

“Contracts involving political events ultimately commoditise and degrade the integrity of the uniquely American experience of participating in the democratic electoral process,” CFTC chair Rostin Behnam said at the time.

He warned that allowing such trading would push the CFTC beyond its mandate and expertise, giving the role of “election cop”.

In the end, resolving the question could well be another election bet.

People concerned about their gambling, or the gambling of friends or family, can find support on the BBC Action Line